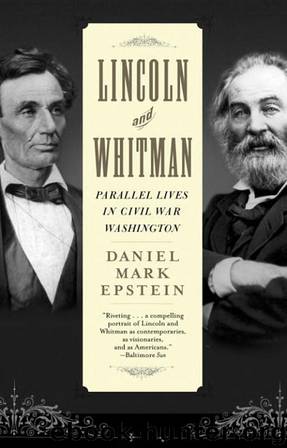

Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington by Daniel Mark Epstein

Author:Daniel Mark Epstein

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: United States, Presidents & Heads of State, Literary, Nonfiction, Biography & Autobiography, History, Civil War Period (1850-1877)

ISBN: 9780307431400

Publisher: Random House

Published: 2007-12-18T06:00:00+00:00

Whitman wrote to his mother: “One’s heart grows sick of war, after all, when you see what it really is—every once in a while I feel so horrified & disgusted—it seems to me like a great slaughterhouse & the men mutually butchering each other . . .” Perhaps this was the sentiment that paralyzed Meade’s generals. “Then I feel how impossible it appears, again, to retire from this contest, until we have carried our points.” He felt it “cruel to be tossed from pillar to post” in these conflicting emotions.

“It is curious—when I am present at the most appalling things, deaths, operations, sickening wounds (perhaps full of maggots), I do not fail, although my sympathies are very much excited, but keep singularly cool—but often, hours afterward, perhaps when I am home, or out walking alone, I feel sick & actually tremble when I recall the thing & have it in my mind again before me.”

One evening Whitman went with the O’Connors to visit the Unitarian minister William Ellery Channing. Channing found the usually calm poet in a state of extreme agitation, pacing restlessly and wringing his hands.

“I say stop this war, this horrible massacre of men!” Whitman exclaimed.

“You are sick,” the minister said. “The daily contact with these poor maimed and suffering men has made you sick; don’t you see that the war cannot be stopped now? Some issue must be made and met.”

Whitman was not alone in his disillusionment. In the Midwest, white mobs attacked conscript officers in protest against Lincoln’s “war for Negro freedom.” In mid-July came the incendiary draft riots in Manhattan. A crowd of workingmen, mostly Irish-Americans, set fire to the draft office. Then they went on a rampage, looting saloons and seizing rifles from an armory on the way to the Negro ghetto where they burned Negroes and hung them from lampposts, killing hundreds. They torched an orphanage. It took the police force, militia, naval forces, a company from West Point, and a detachment of soldiers from Gettysburg to restore order.

In Washington the general feeling was that New York should be cannonaded and the rioters all hung in a body. The President was ill over it, could not even bring himself to convene his cabinet on the sixteenth. “None of us were in the right frame of mind for deliberation,” said the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, “—he [Lincoln] was not.” Whitman, weary of the war, feared the draft, feared that his brother Jeff might end up in uniform, and did not lack sympathy with the rioters. “I remain silent, partly amused, partly scornful, or occasionally put a dry remark, which only adds fuel to the flame—I do not feel it in my heart to abuse the poor people, or call for rope or bullets for them, but that is all the talk here, even in the hospitals.”

The poet was ailing in several ways. He was lonely and home-sick. William and Nellie O’Connor had moved out of the house on L Street that summer, and Whitman was spending entire days and nights at Armory Square in flight from solitude.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15365)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14523)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12405)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12101)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12036)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5795)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5415)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5312)

Paper Towns by Green John(5196)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5013)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4509)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4451)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4398)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4353)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4330)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4208)